Do people obey the orders of authorities, even if they know that these orders are brutally unfair?

Psychologist Stanley Milgram aimed to answer this question and started his experiment shortly after the trial of Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann, who claimed he was “just following orders” when sending millions to their deaths.

Milgram wanted to find out: Would ordinary people also follow harmful instructions from authority?

How did the Milgram experiment start?

"Persons Needed for a Study of Memory. We will pay you $4.00 for one hour of your time."

This ad was in the New Haven Register, a local Connecticut newspaper on June 18, 1961.

The ad invited participants aged 20-50 from various occupations, including factory workers, city employees, laborers, barbers, businessmen, clerks, professionals, and telephone workers. High school students and college students were excluded from the offer.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

Photo by Markus Spiske on UnsplashWhat was the setup of the experiment?

Subject viewpoint:

Participants were told they were part of a scientific study, "The effect of punishment on learning," conducted by Yale University.

There were "teachers" and "learners".

As a teacher, a participant would read word pairs.

When a learner remembered the correct pair, they were given the next one.

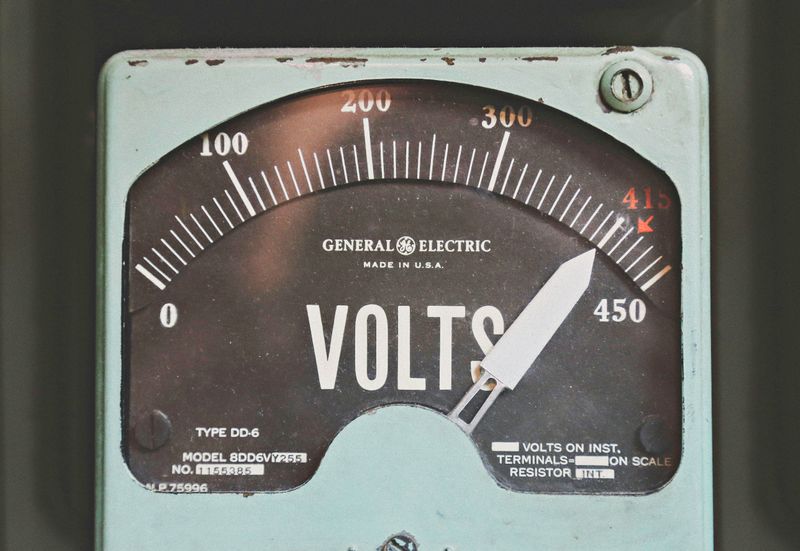

If a learner made a mistake, a teacher would administer an electrical shock, increasing the intensity for each mistake from 15 volts to 450 volts.

The experimenter was a figure of authority whose primary purpose was to ensure that teachers continued the experiment.

Photo by Thomas Kelley on Unsplash

Photo by Thomas Kelley on UnsplashActual experiment:

Teachers didn't know that the learners were actors. Learners weren't given actual electric shocks, but they used scripted pleas to try to stop the teachers from administering shocks.

The experiment tested subjects' obedience to authority — specifically, how far an ordinary person would go in obeying instructions and administering electrical shocks to people.

An experimenter-actor was there to play his part by saying things like, “The experiment requires that you continue,” and “You have no other choice, you must go on.”

Quiz

If someone gets 300 volt electric shock, what does this experience feel like?

What results were expected?

Milgram and his colleagues anticipated that:

Very few people would obey orders to administer dangerous or extreme shocks.

Only about 1–2% of participants (maybe those with sadistic tendencies) would go all the way to the maximum 450 volts.

Milgram hoped that most people had strong moral values that would stop them from harming others.

He also expected that Americans, especially in a democratic society, would not blindly follow authority.

What were the results?

65% of 40 subjects administered the full 450 volts to learners who were screaming and asking for mercy.

Some subjects gave the 450-volt shock 3 times, and only after a learner's frightening, silent reaction caused them to stop.

Many subjects looked relieved and upset after the experiment, showing they felt bad about obeying orders they knew were wrong.

The documentary footage below of the experiment shows one of the subject's reactions:

How are the results of the experiment relevant to real life?

Many subjects who were willing to administer the maximum 450-volt shock justified their actions by pointing to the authority of the experimenter, trusting that “the Yale scientist must know what’s right.”

Milgram reflected on this deeply unsettling result in his book, writing:

The most fundamental lesson of our study: ordinary people, simply doing their job, and without any particular hostility can become agents in a terrible destructive process.

So we'd better...

Lessons learned:

We’re all part of groups — school, teams, or community — and sometimes you need to follow rules to get things done.

But we shouldn’t follow orders blindly. Asking “Is this right?” helps protect your values.

No goal is worth doing that you know is wrong.

In Milgram’s experiment, 35% of people chose to stop. They trusted their judgment. You can too — think for yourself and speak up when something feels wrong.

Quiz

You’re on the school track team. Before an important competition, your coach pulls you aside and says, “If one of the other runners gets ahead of you, don’t be afraid to bump them a little — just make it look like an accident. We need to win.”

Take Action

Your feedback matters to us.

This Byte helped me better understand the topic.